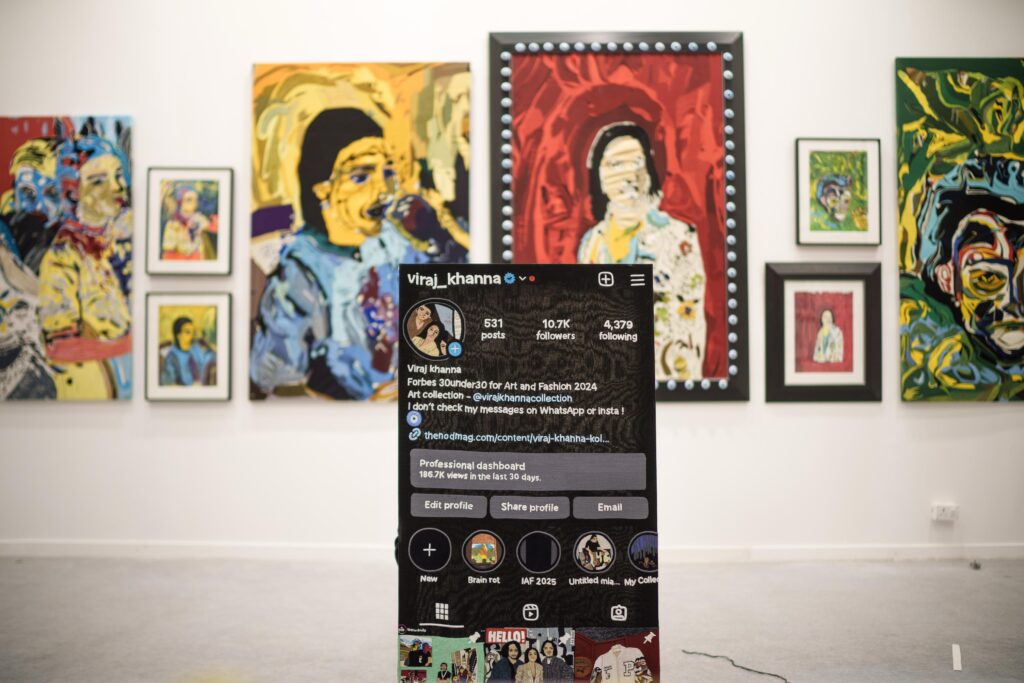

When Viraj Khanna began cutting up fashion magazines on his terrace during the lockdown, it was meant to fill a content gap on Instagram, not spark a full-fledged art practice. But one month, a set of collages, and a sold-out debut exhibition later, things took a different turn. Since then, Khanna’s work has been shown at major fairs and galleries, expanding into sculpture, textiles, embroidery, photography, and even screen-time-themed artworks that stitch our digital compulsions into literal thread.

Art Fervour sat down with Khanna to talk about what keeps his practice in motion: the balancing act between business and art, the collaborative chaos of embroidery, and how humour, discipline, and a quiet sort of bravery shape the way he works, and scrolls.

- Fashion was the plan, art was the accident, but now they’re both happening at once. What does it feel like to hold two creative lives, especially when one started almost by chance?

“Most of my time, around 70 to 80%, goes into running the finance and management side of AKOK and AK, our family business. Whatever time I’m able to carve out beyond that, I shift my focus to art. It’s always a constant shift back and forth.”

That division started early. “Growing up, it was always understood: my twin would do design and I’d do finance. That was how it was set in our heads.”

His studio sits inside the AKOK office, where he moves between spreadsheets, swatches, budgets, and embroidery. “My art studio is literally inside the office. So I go in with my laptop, go through the day, and shift to embroidery or artworks when I get time. It’s all happening side by side.”

What reads as multitasking is actually a tightly choreographed rhythm, one that allows Viraj’s business side to coexist with the whims of an experimental practice.

- Since you began creating collages, your use of materiality has shifted quite a bit. From cut-outs and paper to sculpture, embroidery, what has shaped those transitions for you?

“The collages used to form the blueprint for my sculptures, like a tech pack. That’s why the sculptures also look sort of broken up in parts, sort of glued together.”

Viraj’s early fascination with collage artists like Hannah Höch sparked a practice rooted in instinct. These experiments evolved into sculpture and then embroidery, an area he was already familiar with from working in fashion production.

“Initially, even the textiles were recreations of the collages. That was the first two or three years. Now it has changed. Now I’m working on different concepts, a lot to do with photography, social media, and commenting on Instagram.”

As he became more fluent in the medium, he began to stretch its possibilities. “I started using the khakha, the stencil tool meant for embroidery, to paint. I’d pour paint through it onto paper and then paint inside the outlines. Using a tool meant for one thing in a completely different way, that excites me.”

There’s something cheeky and precise about this approach, retooling craft techniques meant for couture into subversive commentaries on validation and perfection.

The creative freedom textile offers comes from how well he understands it. “With textile, because there are so many different materials I can use, I can use each material to convey a different feeling or emotion. Sequins make something feel extravagant. Thread can be more subtle.” He’s currently working on a new embroidered series. “I’m working on a bridal show for Rajiv Menon, based on my best friend’s wedding. It’s embroidered, it’s funny, it’s personal.”

Viraj Khanna, ‘guilty Only Cuz Of Screen Time!’ Fibreglass Sculpture On Embroidered Astroturf, (L), ‘woke Up Like This’ (R), Fibreglass Sculpture, Courtesy Of The Artist

- You’ve got Art Dubai, a solo in LA, more shows in New York, and an MFA in Chicago, how do you even keep track? What does your year actually look like right now?

“I’m in Calcutta right now. I have a show coming up with Latitude 28 for Art Dubai. They’re putting up a couple of pieces there. In June, I have a solo with Rajiv Menon in LA, and there are some more shows towards the end of the year in New York, with a New York-based gallerist. So there’s a lot happening, and I’m travelling. June and July, I’ll be in Chicago. I’m graduating in July.”

On his MFA at SAIC: “It’s a low-residency programme. Two months in a year I’m there, the rest is online.”

- You began as a self-taught artist. Now you’re doing an MFA in Chicago. Has studying art in a formal setting changed what you take seriously, or what you’re willing to risk?

“There are so many ideas I would’ve dismissed earlier that I now pursue. Like when I started working with Instagram posts and likes, I remember showing it to people and they were like, ‘What are you doing?’”

“That’s where the education helped. I probably would’ve dropped the idea , but now I can see how it fits into the larger art historical context. It’s given me the confidence to take new ideas seriously.”

Viraj Khanna, ‘i Used To Be Sooo Young’, 2024, Embroidery On Cotton, In The Collection Of Michael And Susan Hort, Courtesy Of The Artist

- Textile carries generations of technique, and your pieces often build on that through contemporary forms. What has working closely with artisans taught you about letting process lead the way?

“It’s always happening. It’s a collaboration, a complete collaboration. So many times I’ll say, ‘Do this,’ but they’ll have their own ideas like, ‘No, this will look better, let me try it,’ and it actually does look better.”

The visual language and concept are his. But the technique, the material, the making, it’s shared. “They’re doing it with their hands, they know the craft.”

Sometimes the ideas come from the studio floor. “Things keep evolving and the work keeps getting better because of that.”

There was even a moment of resistance: “There was one karigar who brought the piece back and said everyone in his village doesn’t want to do it. It was an abstract figure, and because of superstitious reasons, they thought it was scary.”

This kind of collaboration doesn’t follow a fixed script. It takes shape slowly, with trust, improvisation, and the confidence to let the work move in its own direction, sometimes away from the original plan, sometimes better because of it.

- Your works are massive, embroidered by hand, and built to last. How long does one take to make, and how do you think about care and longevity, especially in a medium where the work can literally be dry cleaned?

“Some pieces have taken three, four thousand hours, maybe five. It’s calculated based on the number of people working and the time.” He’s candid about the scale: “It’s all hand embroidery. So it’s slow. But I try to think as much as I can before we begin, because changing things midway takes another 100 or 150 hours.”

For younger artists navigating time, scale, and patience, Khanna’s response is a quiet reminder that the process is rarely efficient. The work builds slowly, layered by hand, often over weeks or months, carried forward by a team, but driven by endurance.

And while they look delicate, the pieces are surprisingly durable. ‘I haven’t had a single issue with them getting spoiled, as long as they’re kept in a well-ventilated space,’ he says. ‘Even if there’s a mark, we can just dry clean it. People are usually shocked when I say that, but yes, you can dry clean the artwork, and it comes out completely fine.’

Compared to oil paintings, which he says can crack or fade, textile has proven to be unexpectedly sturdy. ‘We just brush off the dust, keep the space casually air-conditioned, it’s actually been really easy to manage.’, layered by hand, often over weeks or months, carried forward by a team, but driven by endurance.

Viraj Khanna, ‘i’ve Put The Nazar 🧿 Sign Now… So I Can Keep Sharing The Images From My Parties And Holidays Without Stress’, Embroidery On Cloth, Courtesy Of The Artist

- You’ve stitched captions, screen-time stats, and even your own anxieties into your work. What keeps pulling you back to social media as a subject and what does it let you say that you wouldn’t otherwise?

“The art I make reflects how I see the world. It’s not a direct commentary, but I’m always pulling from what’s happening around me. With the social media pieces, I started distorting faces, multiplying them, collaging them, it felt like a way of showing how little we reveal of ourselves online. You’re always seeing someone’s perfect light.”

“We live in a world where your image represents you. More people know me through Instagram than in person. That becomes your reference point, your identity.”

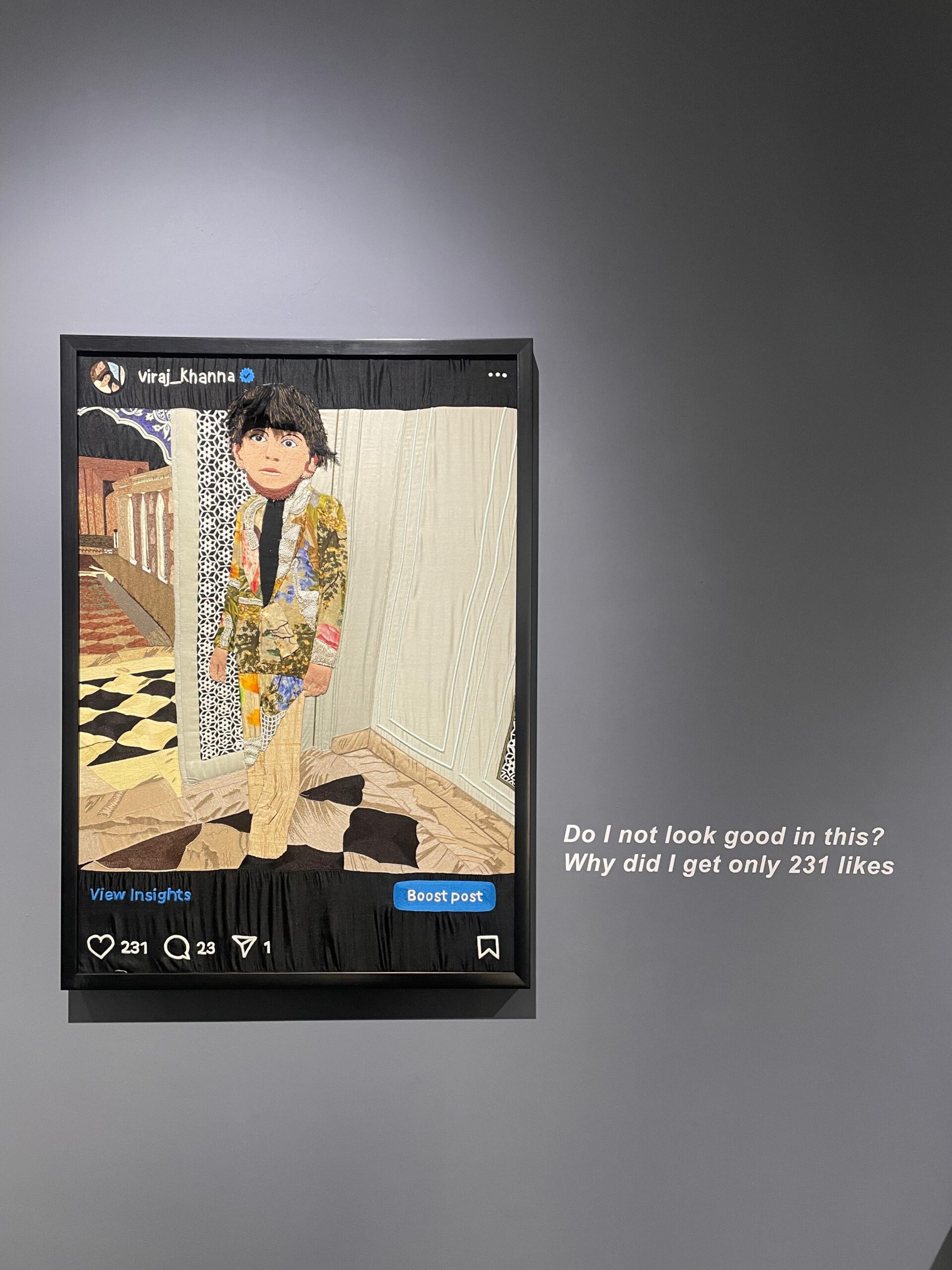

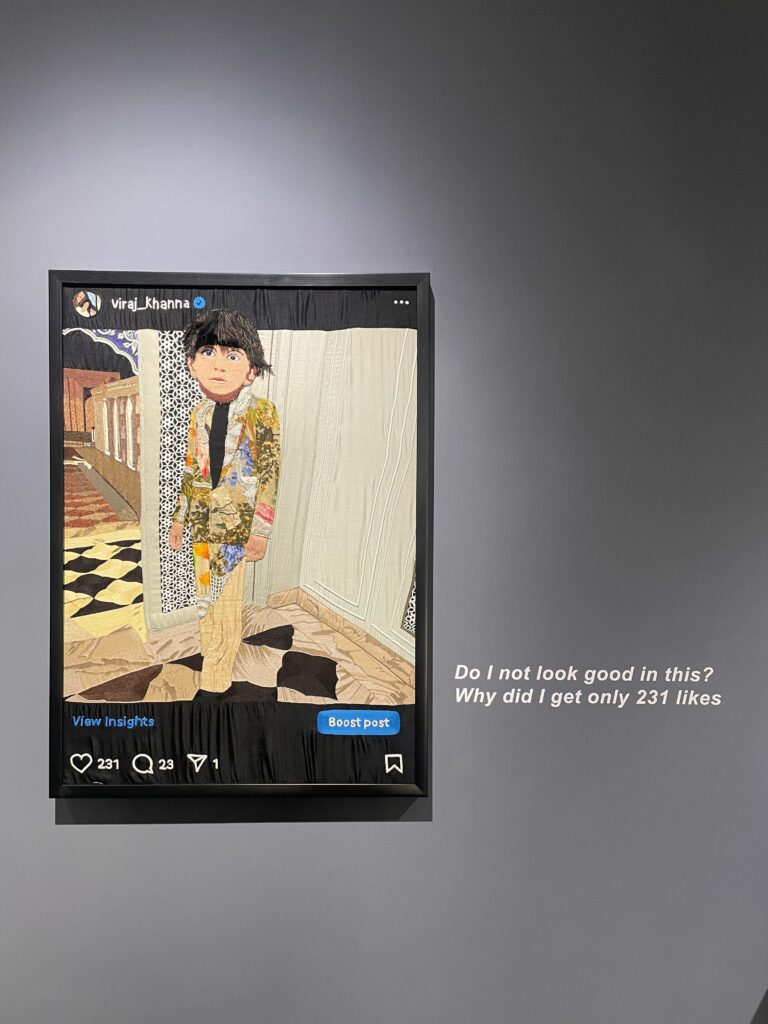

That’s where the stitched screenshots and captions come in. “There was a post that got 231 likes. So I titled the artwork: ‘Why did I get only 231 likes?’ Or when I won an award, I made a piece titled, ‘Now people will think I’m a good artist.’”

His show ‘Brainrot’ leaned fully into that feeling. “I embroidered the screen time stats of my friends, seven hours, eight, even nine. And mine was over seven too. It made me think about how social media shapes not just our self-image, but also our anxiety, our craving for something new, for reach, for recognition.”

That craving rarely ends. “You do a show, and the next day you see someone else’s show online and wonder, why am I not there? You quit Instagram. Then you go back. Quit again. Go back again.”

For Viraj, social media isn’t just a theme of his artworks, it’s a part of the medium. His work doesn’t lecture or explain but rather it lets you sit with what’s already familiar. The screen, the scroll, the voice in your head you pretend isn’t there.

Viraj Khanna, ‘do I Not Look Good In This?’, Hand Embroidery On Cotton, Courtesy Of The Artist

- From steering through early criticism to showing your most personal work in ‘Brainrot’, how do you deal with vulnerability, validation, and staying true to your instincts as an artist today?

“I got a really negative review once, even though the show had sold out. It was online, and I think my gallerist was scared to even share it with me. But I just accepted it. I follow this critic, Jerry Saltz, who says artists need thick skin. Not everyone’s going to like your work. You need courage to keep making what you want to make without getting swayed.”

Criticism, especially early on, hits hard. “You spend six months on a piece, and then it doesn’t sell, or people just don’t get it. That takes patience. And it takes belief in your own process, which isn’t easy when you’re just starting out.”

To stay grounded, Viraj leans on a circle of trusted people. “I doubt myself constantly. Is this good enough? Should I keep going? I share everything with my family, my twin, and close friends. I need that external validation, someone to tell me, ‘Keep going.’ Otherwise, it’s really easy to convince yourself something isn’t worth finishing.”

But that feedback doesn’t dictate his choices. “Sometimes I listen, sometimes I don’t. I’m always looking at art, always thinking conceptually. Others might just respond to what looks good. That balance helps.”

What keeps him steady is process. “I think the reason I don’t get creatively stuck is because I work intuitively first. I start, and then I think. That flow helps generate ideas, once I’m in it, I get momentum.”

That mix of doubt, trust, and structure is what gives Brainrot its pull. The work doesn’t just reveal the scroll, it quietly reveals the artist behind it.

- In your work, you bring a sharp sense of humour, even self-deprecation. Do you find humour helps people connect more easily to what you’re doing?

“I like being humorous with my posts. I usually place the captions directly next to the artwork so people get where I’m coming from. It’s not just a title or label, it helps them understand the thought behind the piece.”

For Viraj, the caption is part of the composition. The stitched text, the statistics, the absurd phrasing, they’re not afterthoughts. They’re clues. He draws you in with humour, then stays with the discomfort of what it’s pointing to.

Take ‘Brainrot’ for instance: screenshots embroidered with anxious honesty, stitched timelines of screen time, a work titled “Why did I get only 231 likes?”, and another that reads, “Now people will think I’m a good artist.” His most disarming details often sit in plain sight, next to captions that sound almost throwaway, until you realise they aren’t.

There’s wit, yes. But it’s also a form of record-keeping, a way of mapping private anxieties within public behaviours. Because behind the perfect grid is a pattern most of us already recognise.

Viraj Khanna, ‘Untitled’, 2025, Hand Embroidery on Fabric, Courtesy of Latitude 28

- You’re surrounded by materials all the time. Are there any you’ve come across recently, something unexpected, that’s made you wonder, could this work in art?

“I’ve been working with artificial leather and artificial leaves. Now I’ve been thinking about using Swarovski and artificial jewellery. We’ve been using these materials in our clothes. Shakira recently wore one of our pieces internationally. I see those materials and wonder, can they work in my art?”

This appetite to remix materials, formats, and tools is what keeps Khanna’s work evolving. For him, the glitch, the scroll, the stitched caption, all become part of the artwork’s vocabulary.

Get to Know Viraj- Off the Clock: Honest answers, strange details, and an unexpected review

What’s your ultimate comfort dish when you’re in Kolkata?

“Home food. Dal, chawal, vegetables. I don’t eat roti. Just rice and vegetables.”

What’s one thing people always get wrong about who you are?

“That I party a lot and I’m very social. I’m absolutely not social.”

Have there been moments when your twin has unknowingly taken your place in the art world?

“Yeah. At my second solo at Tao, I got nervous and left. He stayed and explained the work to everyone. Everyone’s always confused. ”

What’s one thing you always carry, whether or not you end up using it?

“Whole Truths bars. Gluten-free and dairy-free bars I carry when I’m hungry.”

Is there a fashion trend you’d actually draw the line at? Or is anything fair game?

“I’m open to everything. If it pushes the boundary of fashion or personal style in any way, I’ll wear it.”

What’s your version of ‘doing absolutely nothing’ after a long day?

“I go to the gym. Then I actually watch a lot of art walkthroughs of Frieze, Art Basel. Two-three hours a day. It calms me down.”

Has anyone ever interpreted your work in a way that completely surprised you?

“My friend showed one of my works to a palm reader. The palm reader said, ‘This artist came out of confusion.’”

Next up: Art Dubai with Latitude 28 and a solo at Rajiv Menon Contemporary in Los Angeles. Viraj won’t tell you what to feel, but he’ll give you enough to stop, look twice, and maybe laugh before it sinks in. Nothing loud or too obvious, but that’s exactly the point!